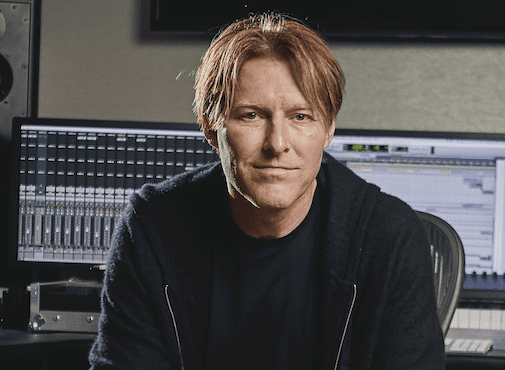

In an already booming music scene, Manchester’s legendary Star and Garter has earned its place in gig and club night infamy. We spoke to the man behind it all, Andy Martin, about what got him into the industry, the Star and Garter throughout the years and the challenges of running a music venue.

[like_to_read][/like_to_read]

S] How did you get started?

A] “I used to write for computer magazines. Then I went to see Half Man Half Biscuit at the Boardwalk in Manchester, which is flats now, I believe. I got talking to the manager there, who was selling merchandise, and I bought a couple things off him and said if you ever do a gig in Manchester again, I’ll come give out flyers. He said okay, thanks a lot. I spoke to him again on the phone and he brought it up again a few months later. He said, do you want to come out and do that? I had never done it before. I mentioned venues to him and he suggested the Star and Garter because he heard good things about it so I rang The Star and Charlie answered. I said I want to put this band on in October and he said what day of the week and I said a Friday and he said, oh I don’t know. He asked the name of the band and I told him and he said pick any Friday.”

S] From then to now, how do you feel about the reputation that it’s garnered over the years and its influence on the Manchester music scene?

A] “I suppose because I’m on the other side of it so I don’t know what reputation it has. I don’t go out into the streets of Manchester and ask about it. It’s either you have heard of it or you haven’t. To some people, it’s really important. You have people who have been coming to Smiths night for years, barristers that have started here, bands that have started because they met here. If I wrote them all down, I could acknowledge we have a fairly decent reputation. I tinkered with Myspace a bit, then Facebook came and I stayed away from that for a few years, but you have to accept it. As a marketing tool, it’s very good. For the most part I can’t stand Facebook, but for marketing, it’s brilliant. When Smiths night and Belle and Sebastian night started we would go out and do posters. We did that for five days and got word out. Now you put it on Facebook and Twitter and it gets reshared. You can rely on getting at least 40 people. As far as reputation is concerned, I’m always very wary. I don’t go online and spout things that are political. You have to be impartial to an extent, otherwise you’re not a music venue anymore, you’re a soapbox.”

S] What would be your top tips for any promoter trying to pursue a career in the industry?

A] “We don’t promote the gigs. The only night we ever had was Smile that belonged to us. Everything else is from outside. We always help out. It wasn’t just ‘give us the money and sod off’. That’s where online does a lot of it for you. If you’re putting a band on, they can sell themselves. If you put a band on and they have a Facebook following, push the band to plug the gig. Where club nights are concerned, that’s where you still now have to get out and do posters and flyers. There’s absolutely no question about that. You can’t promote a club night online alone. Make a flyer and put a playlist on it. That will never change. People still want to know what they’re going to hear at a club night. I feel more sorry for people trying to launch a club night than I do for people doing bands. Unsigned bands is a different story. But even then, if you have three unsigned bands, they’ll have a Facebook page and they’re going to have at least fifty people following them. If those three bands on the bill promote it on Facebook and get half of their following in, you have seventy-five people. Once you have people in there, try to encourage them to all watch the gigs or make the bands watch each other. That’s the worst thing, when it’s like a conveyor belt. You go upstairs, you watch your friend’s band and you go downstairs while the next band are on and ignore it. That’s just unfair on the unsigned bands that are struggling to get off the ground if nobody watches them.”

S] From the perspective of managing a venue, what are your biggest challenges?

A] “From the building point of view, it is over two hundred years old. You’re always fighting the building. The roof leaks, there’s damp, things fall down, the electrics always need doing. You have to pay the staff and try and cut your VAT bill. Go buy the beer where it’s cheapest. Then you have to price it so it makes it worth coming in anyway. £4 for a pint. I don’t even drink. When I was first here and started managing there was us, the Roadhouse, Night and Day and Dry Bar. Compared to us, they were massive. Everyone thought everyone would go twenty-four hour serving. Nobody did. There were probably two bars that did. They were wise to do it. It’s a community itself. It’s a good place. It was sensible for them to do that, but the rest of us carried on as normal. As a retailer, the only people this will benefit are the supermarkets because they can afford to go twenty-four hours. Everybody would buy cheap beer at supermarkets and get loaded up and go out. They would spend less in the clubs and bars. They wouldn’t go to the pubs at all, so the pubs started shutting. Manchester got lucky. When all this was happening the Northern Quarter took off and got all the press. We christened it ‘Soho Light’ or ‘Diet Camden’. It worked. When I first started, you needed to get an entertainment license to open late and you had to do all these checks for health and safety and all this crap. It costs you a fortune every year to do it. That changed. You didn’t have to do that if your capacity was under one hundred. All these little venues opened. They could get two hundred in and nobody ever checks. Then the press got onto it, so the Norther Quarter became this huge thing. At that time, Smile was the indie night to go to, but the Northern Quarter ripped off. A million Smiles happened. Basically it killed Smile, so we had to cut Smile back and put gigs on instead. The Smiths night struggled for a few years, but they have a loyal following. The Smiths night will be a legacy. People come to that from Australia and all over Europe. The Smiths, without question are Manchester’s Beatles. I’m a firm believer that when they get around to building the railway station, they’ll start rattling bits of The Star and Garter off. Then they’ll knock it down anyway. As far as its future as a music venue is concerned, Network Rail will sell it on to whoever pays the top price. I think whoever buys it will turn it into a pub with a restaurant. Or it will become a Starbucks or Costa.”

S] What are some bands you’ve seen that you’re really proud of?

A] “Status quo was fine when they did it in 1999 and filled it. I didn’t actually see the gig, I was upstairs taping the football. All the press came, and there were like four camera crews taking it in turns to film them. I was just thinking, you people have never been here and now you have interest in it for an hour of your day before you edit a two-minute news piece about Status Quo. As far as bands that have played here, Low were good. They play The Academy now. Their gig was one hundred people sat on the floor and listening to ambient music. I can’t criticize people for liking a particular type of music. It’s all about taste. There was a band called The Trachtenburg Family Slideshow Players, which was a mum and dad and a daughter. The daughter was twelve at the time and she played the drums. They were incredible. I bought their CD. ArnoCorps were brilliant. Not my kind of tunes, but for a band that it is a whole show. They create an atmosphere. There’s a fellow called Frank Carter who does the same thing. They create a show. Broken Teeth were good. They’re so local. I’ve watched them come into gigs for years. In that sense, it’s nice when you have shows like that and there are people who were coming to gigs in the year 2000. It’s always reassuring if you’re stood on the door when some people walk up and you know some of them. Half the time I’ve known them nearly twenty years and I don’t know their name. I can’t get my head around people who turn up and think of me as some high authority. I’ve always wanted that with the staff, I didn’t want it to be somebody on high. I always want it to be a team. At the end of the night when you have to clean up all the crap that the lovely musical youth left for us to clean up, everybody has their fair share. When you lose that, then you have a bad atmosphere behind the bar and between the staff. The audience notices it and they will suffer.”

S] What are you tips for a new, emerging band coming into your venue?

A] “If you are given a get-in time, arrive at that time. Don’t turn up late or three hours early. When you get in, don’t walk in with no equipment and walk ‘round the place. Get inside, get your shit in and get it setup wherever the stage may be. Always say please and thank you to the bar staff. Always introduce yourself to the sound engineer because you’re in their hands so if you’re a dick, he can do what he likes with you. Always watch the support bands, even if you hate them. Don’t insist on a rider. Don’t expect a rider. Don’t think that because you’ve got a gig, you’re going to have sixty groupies or be fed and watered for turning up. That all comes later. Put the legwork in first. If you’re there as a support band and the headline band have a rider, see if you can get a bit of it by all means, but don’t turn up and want a twenty-four pack of Stella. The venue will see no money. Support the venue because without the venue, you’d have no gig. If you do get some beer, don’t get pissed up before you go on stage. Every time you rehearse, you’re not pissed. If you can pull it off sober, do it, then get pissed afterwards. All the beer and dancing girls comes after the gig. You’re not there for a night out, you’re there to work. You don’t walk into your daytime job and tell the manager to piss off, drinking beer you haven’t paid for. Treat it like a job.”

For more information, visit: http://www.starandgarter.co.uk