As a concept, The Bikeriders is fascinating. The film, based on a true story, is primarily framed around interviews between Danny (Mike Faist), a photographer who documented the Vandals Motorcycle Club in Chicago as a student, and Kathy (Jodie Comer), the wife of one of the gang’s most well-known members. These interviews drive the narrative, which traverses the 1960s and ‘70s, as Danny catches up on everything that’s happened since he last saw the group. As may be expected from any gang-related tale, it hasn’t been all that great.

Much of the film centres around the idea of found family, of community. Misfits find a place in the Vandals, and as the gang grows, expanding into new chapters, everything looks rosy. They host giant picnics, booze-fueled affairs that end in muddy fields, churned up by circling bikes, and physical altercations, both friendly and vicious. This feeling of belonging is strongest in the scenes where tens of motorbikes rumble down the highway in formation, fields or dust as far as the eye can see and the roar of the engines strong enough to shake the cinema seats. The sheer power of these moments is breath-catching, and while the audience will certainly feel a degree of separation from the camaraderie it’s enough to get across the seduction and joy of the Vandals in their early days.

Comer is undeniably excellent in her role. She knows exactly when to play it serious and when to lean into the comic, and her replication of the real Kathy’s speech patterns and tone is uncanny. But aside from her mile-a-minute dialogue, during which she frequently drifts off topic before being gently redirected by photographer-documentarian Danny, the script is sparse. Butler’s Benny is more of a brooder than a talker, the majority of his time on screen spent smouldering into the distance or flying off the handle and punching something. It’s not that he’s not good at this—he excels at the tortured bad-boy schtick—but it leaves a lot to be desired when it comes to the character’s complexity.

Benny is, or could be, an interesting character, but just as he keeps those around him at a distance we never really get to learn what makes him tick. He has a strong if misaligned sense of right and wrong, he’s loyal to a fault and he really, really loves motorbikes. There’s no real emotional depth to him until the final scenes where, after Kathy has made a point earlier of the fact that he never cries, he sits on the front porch sobbing. Presumably this should be a cathartic moment for all involved, perhaps a sign that he’s changed and is finally showing some vulnerability, but it’s such a predictable plot point that it falls entirely flat.

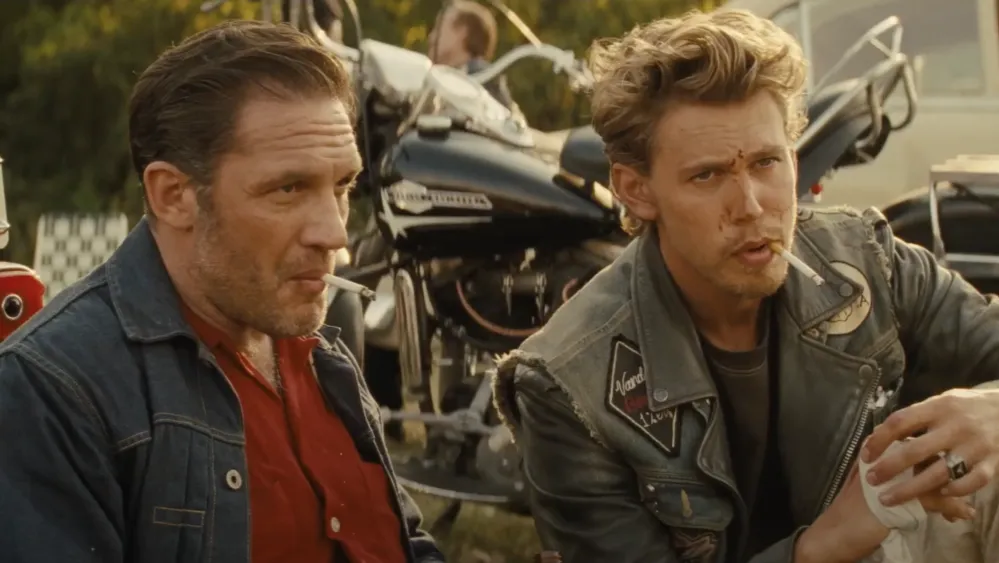

Tom Hardy completes the central trifecta as Villains founder Johnny Davis. Beginning as a man playing dress-up as a gang leader, his gradual descent into violence and serious crime should be interesting, but it’s difficult to get invested in the character’s journey. The only real affection Johnny demonstrates is for bikes, his boys, and Benny, who he’s pretty obsessed with (to the point that he and Kathy end up in a heated argument over who should have custody of the fully-grown man). We’re told that he is, or was, a family man, but we rarely see this family or get to know why it wasn’t enough for him, why he favours the gang over his own flesh and blood. Again, an opportunity for complexity is missed.

Jokes have been made that one of the best parts of a Tom Hardy character is never knowing what his voice is going to sound like. In The Bikeriders, the effect can only be described as startling. Fairly high pitched and almost wheedling at times, it’s occasionally hard to take him seriously as the founder of a biker gang, or even completely comprehend what he’s saying.

In terms of pacing, despite clocking in at just under two hours the final act feels like a drag.

Each new flashback, prompted by Kathy’s interviews, seems both unnecessarily drawn-out and like the film is hurrying to wrap up the loose ends. The reminders that these are, or were, real people are genuinely affecting, speaking to the tragedy of the Villains and nostalgic for what the gang once was: a group of guys who just really loved motorbikes.

The Bikeriders has its moments, but feels incomplete as a whole. There’s style here, and attention to detail—the mimicry of the real Danny’s photos in some of the shots is great—but the film feels just like the photos it’s based on; a series of snapshots that hint at depth but never let us see the full picture.