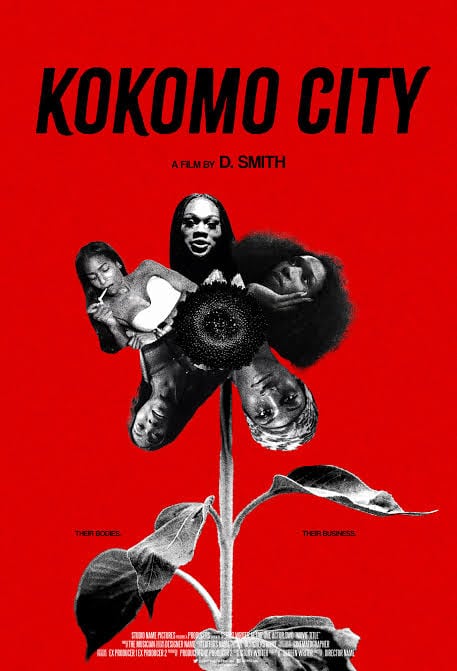

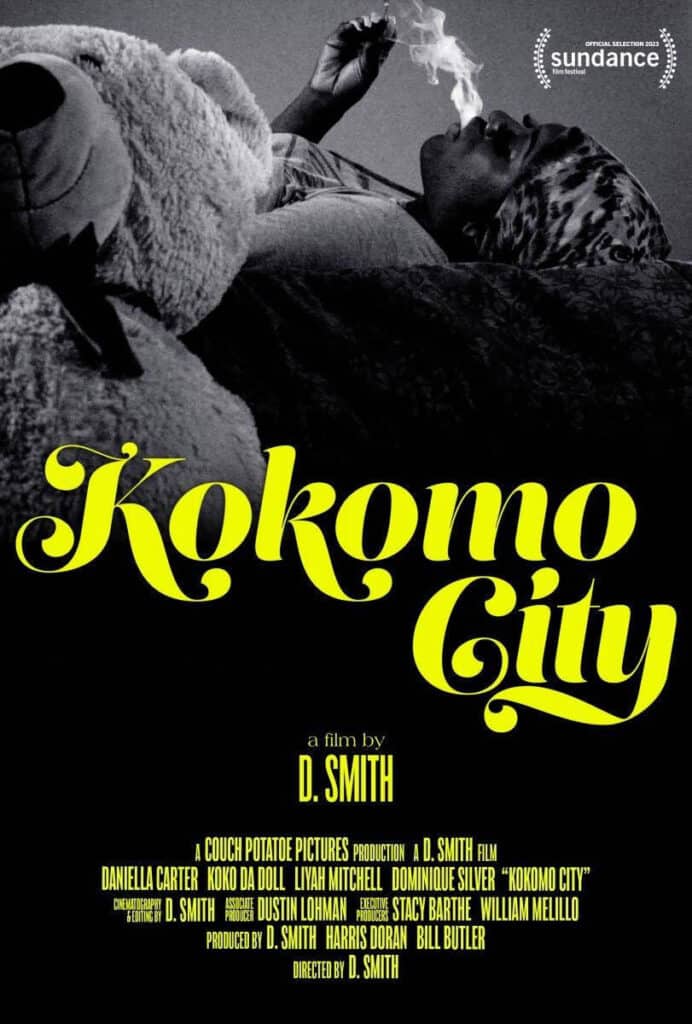

In her conversation with Jeremy O. Harris and Mel Ottenberg for The Interview Magazine on September 19, 2023, the Grammy-nominated composer D.Smith proclaimed that she hated the word ‘taboo’, trying her best to be transparent with her intentions and forgoing another ‘villainizing, condescending, preachy film’. True to the word, her cutting-edge Sundance Film Festival debut Kokomo City (2023) is a landmark film up her sleeves. Ostracized as a trans singer after she came out in 2014, it was a revelation in the life of the singer-songwriter to discover ‘what makes transphobes tick’. Rethinking heterosexual biases and surreptitious compromises in the lives of trans sex workers, the documentary explores the inert ways in which a Black woman navigates within an alien society.

The trans women are forced to mutilate what Janice Raymond calls ‘their native bodies’, in order to circumscribe into the political and life-threatening medical abuse posed by desire. The film tries to explore these maladjustments within the lives of four Black trans women, namely Daniella Carter, Dominique Silver, Koko Da Doll, and Liyah Mitchell. It holds at gunpoint the attack on one’s body as a political symbol of the male supremacist society, while refusing to assign self-determination to any of its bearers. Rightly so, the score mocks the audience, singing aloud – “From raising someone else’s child/ And mine being sold away.”

Smith makes sure the portrayal of Black men in her film transpires beyond the Imposter Syndrome. As second class citizens, they are inherently construed as part of a distant problem, yet it is so close to home that they ‘may be in your home when you are not there.’ Their dangerous existence, recurrently susceptible to AIDS and clientele gun violence, erupts in a distinct fetishism. It is a confession that can only be made secretly. Men who are attracted to trans women deny the fact that they are genetically their counterparts. Until the orgasm, the transfusion of foreplay and cosplay give way to a vicious cycle of resistance and intimacy. Yet, as soon as societal moralism kicks in, the average white man relieves himself of any possible responsibility.

It is an integral part of the film to pay tribute to those who have failed to accept the inevitable changes and challenges of gay sons and daughters. For the already oppressed community, it is a dire need that the son provides what the husband couldn’t. However, the obverse comes alive when the gay son is alienated from the mother and cocoons himself within the bleak distress that the marginalized face as a whole. It’s a marvel that Smith could augment the notion of a supportive maternal authority, when the likes of a hypothetical ‘Madam’ C. J. Walker would never pay heed to the broken Black people of her community.

It is an integral part of the film to pay tribute to those who have failed to accept the inevitable changes and challenges of gay sons and daughters. For the already oppressed community, it is a dire need that the son provides what the husband couldn’t. However, the obverse comes alive when the gay son is alienated from the mother and cocoons himself within the bleak distress that the marginalized face as a whole. It’s a marvel that Smith could augment the notion of a supportive maternal authority, when the likes of a hypothetical ‘Madam’ C. J. Walker would never pay heed to the broken Black people of her community.

The gang culture of masculine favoritism is based on the idea and ideal of procreation. It is the resurrection of a neo-slave mentality wherein lies the core of ‘normal’ experience and regeneration. But, as Judith Butler claims in Gender Trouble, the notion of gender is thought to be prior to culture, a neutral slate for culture to act on. This penetrates deep into the behemoth process of ‘becoming’, a continuous process for the missing voices. Trans women deny this genital matrix of reproductive power. They include the vitality of survivalism in the art of living itself.

The ‘authentic’ is always derived. The original is transfused. Smith leaves her spectators with a hopeful prospect. It is empathy that diversifies all identities. The love denied at home is plentiful in the costumes of the day. Whether you are an Alternate/Anime Girl, Hood Bitch, White College Lass or Nerdy Newbie, the connotations will have space for you. And for a discreet and dignified drag show, go for Hush Nights. After all, ‘you gotta hurt people hurting people.’