Fans of weird cinema can’t get away from Frankenstein’s monster. Just what is it about this creepy creation that inspires so many?

Weird cinema has an obsession, and for once, it’s not David Lynch-related.

Have you ever noticed how many films feature Frankenstein’s monster, or touch on themes from the classic novel? There’s a constant stream of references to the macabre Victorian tale; in the last decade alone, over 40 films have referenced the character directly – from cute kids’ movies to international blockbusters.

Mainstream science-fiction in particular loves a good Prometheus reference, a reflection on what it means to be human, or a chaotic “science beyond our control” parable. We’ve seen it in Blade Runner, RoboCop, Terminator, Alien, Moon… the list goes on. The story itself is ever ripe for adaptation and homage because directors get so much to play with. We clearly crave images of lightning striking mad laboratories, the gory body-horror of a patchwork person, or the inevitably sexy gothic overtones of a Victorian-era flick. Whichever way you look at it, the story of Frankenstein’s monster has truly got us by the neck bolts.

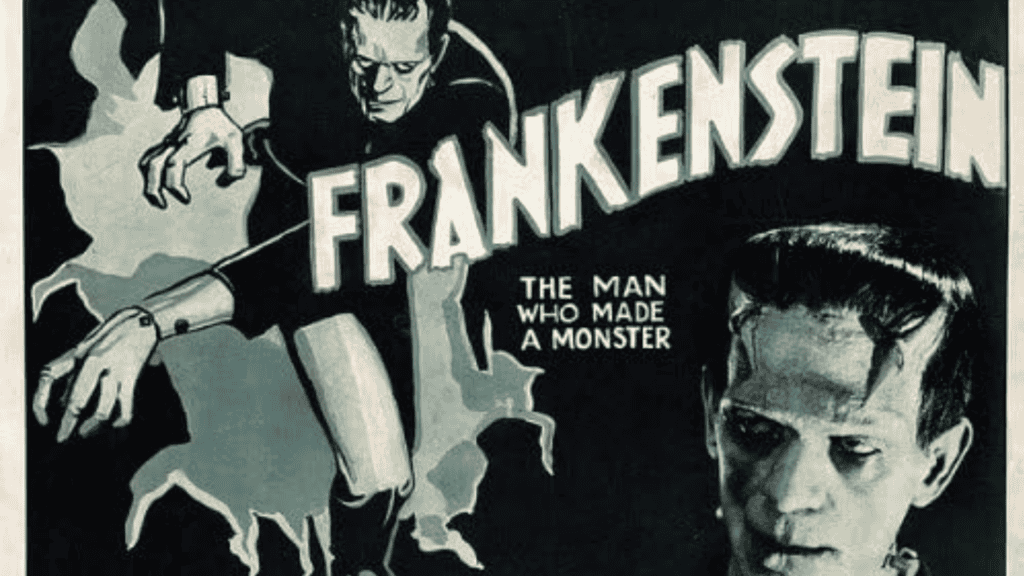

Cinema has arguably done as much for the tale of Frankenstein’s monster as is true in reverse. Many of the classic images we associate with the story are the result of a decades-long game of Telephone, passing down half-whispered ideas until we somehow have an iconic figure with very little in common with the original text. The film industry has enriched Frankenstein and his monster with ideas we can’t now separate out: the stocky cylinder of a head, the neck bolts, the patched up green skin, the shambling, lumbering malevolent creature – but none of it comes from Mary Shelley herself.

In fact, in Shelley’s book, the creature was far from the hulk-like tapestry of flesh we see reflected in Halloween costumes today. He was intended to be beautiful, created by the young scientist Victor Frankenstein to be the perfect embodiment of a man – peak performance, if you will. Tragically, once the creature woke up (not from lightning, from a complex mixture of chemicals), his skin was translucent and stretched thin over visibly working muscles and organs, and he had two unsettlingly watery eyes, flowing black hair, and black lips. Victor decided, based on looks alone, to abandon the poor creature. Alone and afraid, the creature takes itself off and teaches itself how to read and communicate, proving itself to be intelligent and predisposed to kindness. Over time, it’s the actions of those around him who drive him to revenge, making the tale a tragic one of abuse and innocence lost.

The first time we saw the creature on film was in a 1910 short film, but perhaps the most iconic performance was that of Boris Karloff in 1931, informing generations of horror-fans as to how the misunderstood monster should look. Mainstream adaptations have given us straightforward interpretations of the classic story, but when writers and directors decide to get weird and subversive with it, we see a split into three categories: whimsical Victoriana, grotesque body-horror, and camp kookiness. Weird cinema just loves this creature.

The whimsical Victoriana category is fully on display in Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things (2023), which was based on the 1992 novel by Scottish author Alasdair Gray. The film differed considerably from the novel, which had more in common with Shelley’s tale, but still paid clear homage to Frankenstein’s monster. Unusually for Lanthimos, the film wasn’t particularly gruesome or body-horror focused, instead centring on the loss of innocence angle, and dialling up ye olde English whimsy as high as possible. By moving away from a classic Frankenstein’s monster portrayal, Poor Things was in some ways more accurate – portraying the ‘creature’ as athletic and energetic, as well as empathetic and intelligent. Someone we’d all like to be, had the world not crushed our spirits.

Go back in time a little and you’ll find more focus on the grotesque body horror element. Both Splice (2009) and The Fly (1986) play into these themes in different ways, and have become gross-out favourites for many weird-cinema connoisseurs. The less said about Splice the better, perhaps – it’s a deeply grim and misanthropic film of questionable quality – but it captures perfectly the anxiety that Shelley’s scientist represented. The two scientists create an abomination, which they raise as their own, initially feeling protective and loving toward it before rejecting it based on its uncontrollable nature. Much like in the original story, this creature doesn’t stand a chance in a world unprepared for – and disgusted by – its existence.

The Fly takes a different approach, instead spinning the camera around on the scientist himself, who undergoes a horrifying transformation and becomes the monster. As a million GCSE English students will now be screaming in unison, the original story also uses this concept as a metaphor – who is the real monster? In Shelley’s time, the idea of science unconfined was just as scary as it is to us now.

Finally, you’ve got the cherry on the cake: the camp and kooky adaptations. These ones are unashamedly fun, tacky, and really lean into the inherent silliness of sci-fi and horror tropes. The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) famously lampooned as many of these tropes as possible, with Rocky Horror himself filling the role of the Frankenstein’s monster pastiche. Moving away from the cliched green giant, Jim Sharman instead wrote him as an ‘ideal male’, much like Shelley’s original vision dictates. Once again, there’s nothing wrong with him, it’s society that has the problem.

More recently, Zelda Williams’ Lisa Frankenstein (2024) made it all about sex, revenge, and teenage angst – casting Cole Sprouse as a bedraggled Victorian lover resurrected by an electric tanning bed. Draped in neon and adorned with some very ‘80s hair, Lisa Frankenstein is a gorgeous gore-fest that polarised reviewers. We get some doomed teen romance, some evil-stepmother narrative, and a Carrie-esque all-out revenge finale, though, so weird cinema fans are eating well with this one. Despite using the name directly, the only thing this film has in common with the original book is the fact the main character has a dead mother. Everything else is a mish-mash of more recent tropes from the deep bank of schlocky horror cache.

More than 200 years since the book was written, it’s clear Frankenstein’s monster is here to stay. Not the original sallow-skinned gentle giant, perhaps – but a more modern form of the cast-off creature is destined to be resurrected over and over for our cinematic pleasure. Whether we relate to a loss of innocence through societal pressure and unkindness, to themes of abandonment and ‘otherness’, to a deep desire to be loved despite all our flaws, or even just harbour a love for creepy Victorian aesthetics: the kooky, campy, tragic world of Mary Shelley’s darkest creation will continue to hold unparalleled weird-appeal.