The relationship of occultism with rock ’n’ roll is one that’s existed since the latter’s inception. Arguably even before that; if the predominately white version of rock that became popularized during the 1950s grew out of the appropriation of the work and traditions of musicians of color, it follows that a conservative white majority would look upon the insistent rhythms of rock as something akin to Paganism or the like. In any case, the conservative majority of the world loves to view rock as, at its most secular, a form of unwelcome rebelliousness against the establishment. It’s an identity that musicians and fans themselves, like all oppressed groups, have taken back and gleefully amplified.

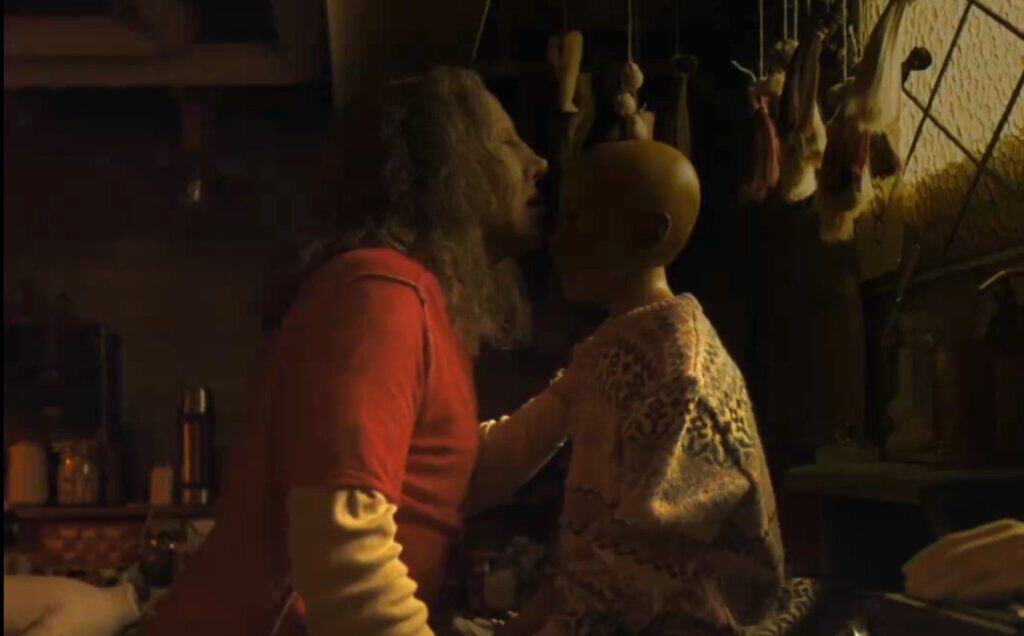

While numerous bands have openly embraced the occult, using Satanic imagery and subject matter in their work, these groups tend to be in the same few subgenres: shock rock, heavy metal, et al. Glam rock, as a subgenre, isn’t usually associated with the occult or with Satanism; if such a comparison is made, it’s typically to do with whatever homo-, bi- or pan-sexual leanings the artists and/or their music may have. That’s why, initially, it’s a little unexpected to see the titular serial killer of Osgood Perkins’ new Satanic procedural horror movie Longlegs be obsessed with glam rock and the band T. Rex in particular. Longlegs (as portrayed with unnerving manic menace by Nicolas Cage) has pictures of T. Rex frontman Marc Bolan as well as Lou Reed (circa Transformer) hanging in his basement lair, where he constructs dolls of real little girls to place inside their homes, thereby literally and figuratively letting in a demonic presence.

Lest we think that the inclusion of glam rockers can simply be chalked up as a Cage character tic, Perkins ensures that the entire film is infused with the sound of T. Rex, particularly their 1971 hit Get It On. A title card featuring a passage from the lyrics of Get It On opens the film, as the sound of an amp being plugged in plays in the background. The song itself in its entirety provides the soundtrack for the end credit roll. The distributor of Longlegs, NEON, has also seen fit to include more references to Get It On within the film’s ominous marketing campaign. With all of this as evidence, it’s clear that the glam rock references in “Longlegs” are not idle or incidental ones.

While name checking T. Rex and Lou Reed in Longlegs is not the same as using, say, Black Sabbath or Judas Priest, glam rock does have more connections to the occult than one may initially assume. David Bowie, the other major pillar of glam after Bolan, made a reference to Aleister Crowley (the late 19th/early 20th century occultist) and his Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the song Quicksand from 1971’s Hunky Dory. Electric Light Orchestra, in addition to writing songs rife with allusions to mythology and fairy tales during the early part of their career, fooled around with Satanic Panic-baiting backward masking gags on a few of their albums (including, not coincidentally, Secret Messages). Of course, we can’t overlook the Knights In Satan’s Service, AKA KISS, a band who put together glam, pop, and shock rock arguably better than anyone. Before Queen became world-renowned as a premiere arena rock band, they were a very nerdy prog-influenced group with songs like The Rat King and The March of the Black Queen. Speaking of prog, King Crimson’s output merged Huxley “doors of perception”-style fantasy with imagery that could be viewed as occult, such as with their 1974 single Starless. That song opens the film Mandy, a movie involving a Satanic cult of musicians which stars — surprise, surprise — Nicolas Cage.

Rather than mining glam rock for any deep seated occultism, however, it’s entirely possible that Perkins uses it in Longlegs as a pop culture artifact whose general wholesomeness is turned sour and threateningly evil thanks to the Satanic context. This possibility is further supported by the way Longlegs himself is discussed by FBI Special Agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe), where she lumps the ritualistic killer (whom she believes is using accomplices) in with infamous contemporaries, most famously Charles Manson. Manson, of course, along with his followers known as the “Family,” had ties to both The Beach Boys and The Beatles, two groups whose public image was more squeaky clean than Squeaky Fromme. When the Tate-LaBianca murders occurred at the hands of the Family in 1969, the various references to the Beatles’ “Helter Skelter” as well as Manson’s relationship with Beach Boys’ drummer Dennis Wilson lent both groups’ music a sinister aura they didn’t previously contain. Thus, given that Get It On is T. Rex’s biggest hit, the type of single that can live comfortably everywhere from supermarkets to roller discos, it initially seems that its use in Longlegs adheres to this “corruption of the familiar” aesthetic.

Yet to say that T. Rex, Marc Bolan, and Get It On itself aren’t aligned with the occult would be inaccurate, too. The band’s early output, back when they were known as Tyrannosaurus Rex, featured mythology-heavy lyrics (especially tunes like King of the Rumbling Spires) as well as drummer Steve Peregrin Took, whose name is a reference to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings character. What’s more, in 1969 Bolan published a book of poetry entitled Warlock of Love, filled with passages that would make the occult-obsessed Jeremiah Sand from Mandy envious. In this context, some of the lyrics of Get It On (which is, let’s be clear, a song about sex) take on an edgier connotation. Certainly, Longlegs gets a lot of mileage out of lines like “You’ve got the teeth of the hydra upon you.”

The inclusion of the Lou Reed image from Transformer could simply be an aesthetic choice, too, given how eerie and wraithlike Reed appears in that famous shot. Yet Reed also has some connection with the occult: during his time with the Velvet Underground, he and the band wrote and recorded the track White Light/White Heat, a song whose lyrics have generally been assumed to be about amphetamines. Yet Richie Unterberger’s book “White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-by-Day” puts forth the notion that the song was actually influenced by Alice Bailey’s book of the occult, “A Treatise on White Magic,” which discusses a way of controlling one’s astral body through manipulation of white light. One could say that Mick Rock’s cover shot of Reed for Transformer manages to capture Reed’s astral energy, a quality that would certainly make Longlegs admire the image enough to hang it up in his room.

In a public appearance before a screening of the film in Los Angeles that this writer attended, Cage explained how the character of Longlegs was partially inspired by his own mother, and that inspiration not only suits the thematic aspects of the film, but also accounts for Longlegs’ unnervingly high-pitched voice. Yet Longlegs’ attitude and appearance also recalls the androgyny of glam rock, too. His tousled long hair and weathered skin make him look similar to an aging rock star, something that is bolstered by a moment where Longlegs, driving home after shopping for supplies at a hardware store, begins mocking the checkout girl’s verbal discomfort with his presence, in a way where he’s almost scream-singing in a rock vocal style.

Ultimately, all of the references to T. Rex, Lou Reed and rock n’ roll in general may simply be Perkins’ way of positioning Longlegs the movie as a rebellious, subversive work all its own, co-opting the energy of rock as both a tone-setter and mission statement. As a film, Longlegs thrives in the liminal space between tangible evil and the uncanny, the idea that bad people do evil things combined with a supernatural force that may be compelling them to commit such atrocities. Thanks to decades of panic and propaganda, rock n’ roll will forever be associated with the idea that it might be somehow morally unsavory, similar to the horror film. Whatever the case, us fans of both rock and horror are forever committed. To paraphrase Bolan: they’re both dirty and sweet, and they’re ours.