Choose music; choose to live forever. There are echoes of certain sounds in the fibre of bands emerging long after them which can always be traced right back to the source. Very few bands achieve that alchemy, but Paul Mullen is the founder of not just one of them, but many.

Mullen, a Sunderland native, is known first and foremost for fronting the experimental alt-rock group yourcodenameis:milo. Their forward-thinking sound reflected a future that was leaps and bounds ahead of their 00s heyday. When their debut album bucked the trends of the dominant landfill indie of the time, the 37 copies it sold fell into the right hands, such as Bloc Party and The Futureheads, who in turn went onto inspire countless others. Since then, they have become a staple in the post-hardcore scene with overwhelming commercial success. The tremors of their five-year stint can still be felt in the work of their successors to this day.

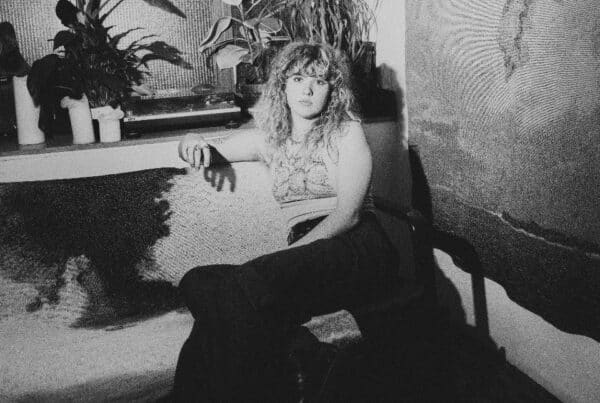

Mullen in 2020 | Pioneertown, California | Image: Chris Corner

Though the band went on hiatus in 2007, for Mullen the grind never stopped. His creative output is daunting, with offshoots in the form of the riotous Losers, Young Legionnaire, Bleach Blood and HorseFight, among many others. Speaking to him from the aptly named Pioneertown in California, he has decided to hunker down through lockdown in the studio. He’s been enjoying shaking off the feeling of not missing out, taking stock and spending some time toying with “silly little ideas” – ideas that we both know are bound to grow into yet another timeless record and one more sell-out tour. It’s all just a day’s work for Paul Mullen.

“Being here and creating sort of is my life,” he says, gesturing to the set-up behind him. “What do I enjoy outside of music? Murder mysteries on Zoom”, he jokes wryly. When he’s not preoccupying himself with screen-to-screen lockdown pass times, he quite casually shares that he has made and finished an entire record. Never able to rest, he has already started the blueprints for his next musical scheme, something that he’s been wanting to do for no less than fifteen years: a solo project. “I have an acoustic guitar here”, he says, waving it, “and I’m in the desert in California. It would seem a bit wrong if I didn’t try my hand with some acoustic numbers, you know?”

Combing through years’ worth of archived voice notes of half-formed ideas, he’s trying to build the foundations of an EP. “I don’t want to say this because I’ll have to make it happen, but I want to do a song a week: write it and then perform it on Instagram at the end of the week.” He puts his head in his hands, moaning, “Why am I doing this? I’m an idiot! I’ve said it now, I’m going to have to do it.

The future looks alluring, but Mullen has something else in mind for the here and now. With gig venues hanging on by a thread in a brutal economic climate brought about by social distancing, one that is close to yourcodenameis:milo’s heart is in dire need of help. The Cluny was the epicentre of where their career took off. “That venue was our second home”, Mullen says. “We’d have record labels come up, and we’d take them down to The Cluny: we had our album launch, our EP launch – everything was there. It was the centre of our band, really.”

Teetering on the brink of closure, now was as good a time as any for the band’s ‘pay-it-forward’ attitude to come to the fore, despite being on hiatus for thirteen years. “It just felt like we could so something. We thought it would be a really good time to give something back to The Cluny,” he says. That ‘something’ was a yourcodenameis:milo reunion show. After reaching out to the band, who, despite having commitments of their own, are still good friends, he found that the same idea had been on the tip of their tongue.

With The Cluny hanging in the balance, it reminded them to take things back to their roots. Dusting off their old repertoire, the band announced a show on their home turf which sold out within a few hours. Due to popular demand, they announced a second show scheduled for September (TICKET LINK HERE). “The shows will happen,” Mullen is determined, “no doubt about it. Whether it’s in September – because obviously we’re not going to do it if it’s not safe – is another thing. Whatever the guidelines are from the government at that time, we will follow. But they will happen. Whoever has a ticket will see us.” A complete reunion isn’t something Mullen is ruling out, but he says the band are taking it one step at a time.

Bringing the band back out of retirement reminds Mullen of just how much it changed his life. “It was the baby,” he says. “It was the band where we did our first radio session, our first Peel session – all these things happened for the first time. The good and the bad: it all happened for the first time with milo.”

yourcodenameis:milo were onto something when they’d had a session with John Peel in London at the BBC before they’d ever played a gig. “It all started with that, really,” Mullen explains. “He heard a demo – well actually, he didn’t hear a demo – because we sent him a CD and it didn’t work. He ended up calling Justin [Lockey, guitarist] and saying, ‘I’m going to make it my life’s work to listen to your CD!’ We didn’t even think it was actually John Peel on the phone, but it was. It was insane. From there, it all happened so fast.”

The band would go on to work with producer Steve Albini, the virtuoso behind Mullen’s favourite record, Nirvana’s In Utero; play shows in Glasgow with such an energy that he still remembers them to this day; and even worked with producer, Flood, who said during a talk he was giving in Berlin that, even now, he still listens to the band’s debut album Ignoto. All of these are achievements he prizes. “It was the freedom we had, looking back”, he says, “which we didn’t realise we had at the time. But now, looking back, some of the fond memories I have was just having the freedom to what we wanted in the studio.”

What yourcodenameis:milo achieved far exceeded any expectation for a band who began outside the cultural capitals of London and Manchester. “With milo, we tried to not go down to London as much as possible in the early days,” Mullen says. “We wanted people to come to us and see our little studio; our little spot; our lives and get a picture of it. We just locked ourselves away, staying in The Cluny, mostly. We just kept to ourselves, locked ourselves in and tried to write the best music that we wanted to hear. We kept going until we got it right. We threw everything at it.”

Though the face music industry has evolved dramatically since yourcodenameis:milo’s heyday, Mullen’s advice for artists on the come-up remains the same: “It’s got to be about the song. In the studio, we always say, ‘When you finish a song, can you stand behind it? Is this you? Are you trying to be something else here, or is this really you? Can you stand in front of ten people and play it exactly the same way as you’d play in front of ten thousand people?’ Because that’s it. No Questions. To get to the level of someone like Bowie, Prince or Bjork, go big; go big because you never question who they are. That’s them, there’s no doubt. If you get a song where you can go, “This is it. I don’t give a fuck what people think in the end of it, because this is a total extension of what I want to do.” It’s very hard to hit, but when you get it, people will see it, and go, “That’s it, I’m in”. I think when I consider how Milo connected with people, there was an element of that. People got it. After 13 years, they’re still here. And some people didn’t get it – and that’s great, that’s fine. Confuse the fuck out of people – we did that a lot. Still do.”

Mullen is always focused on the next thing. “Well, it all seems to be happening now, right at this moment,” he shares. Losers, his vitriolic alt-rock side project, have just finished mastering an EP. Although live appearances are rare, “we’re making noise all the time”, working and writing in the studio every day. The livewire Young Legionnaire, however, have always been “a stop-start thing”. He says, “We’ve always got to be in the same room when we’re writing,” which was made nigh-on impossible with former Bloc Party bassist Gordon Moakes basing himself in Austin, Texas. “It was always very much a ‘turn the tap on, go for it’, kind of thing.”

Every project of Mullen’s is a different outlet for his indomitable creative energy. “When I was living in London with Tom [Bellamy, of Losers], I pretty much said yes to every band I was asked to join or play with. I think I was working with five or six active bands at the time: just writing, playing live and doing studio work. I really enjoyed it. I learned a lot about myself as a writer and a musician. I’ve always been great at bouncing off of other people. I’d still like to keep that element in my career.”

Working tirelessly on projects comes with an inevitable price. “Of course, I’m very emotionally connected to the music I make,” Mullen explains. “So as soon as I put it out there and let it go, it feels like a real part of me has gone with it as well. If it doesn’t get a great response or work the way I thought it would, then it directly affects me and gets me really down. It would just be this massive outpouring of creativity, but then what would come back would be negative. It would just destroy me sometimes, and get me into some really dark places.”

Learning to let go and separate himself from his art is a hard-earned attitude. “The job took over me. I lost who I am as a person – I’m not the job. Sometimes it really felt like a job. Sometimes it feels fucking shit, and you don’t want to go into the studio every morning. But then I had to remember fifteen year-old Paul, who would be punching me in the face if I complained about that. The difference is I don’t let those things come back to me now. I’m still me; my work is only an external part of me. I put a lot into it, and I always will. I’ll keep doing that. Next. Let’s crack on. I try not to let that negative energy come back from something that didn’t work out.”

Mullen remembers the days fondly, when success was measured by the free crates of Fosters he’d be given as payment for the band’s shows. When beer is replaced by adulation from the press, awards and sell-out tours, he admits that “the whole grand system’s idea of success” is “a lot of weight for a band in their early twenties to carry.” For him, success could not be so easily gauged. “Feeling kind of full within yourself – that’s half the battle isn’t it? Whatever you’re doing in life, if you’re feeling good about it and feeling good about yourself, that’s success really. That’s how it should be measured. The simplest way to understand it is: does it make you happy? Are you filled with what you do? You need to figure it out yourself, internally, and then everything else will fall into place.”

Words: Sophie Walker / Interview: Dom Smith

Listen to / watch the interview below: