Words: Callie Petch

In the four prior years that I’d done the London Film Festival, I never went to the secret screening. Around the midpoint, there is always a big secret screening event of some mystery film not on the festival programme with no prior clues or indication as to what it may be until the opening titles kick in. Naturally, it’s a pretty hot ticket and I’ve never managed to get one. Partly this is due to the simple fact that I normally have a lot to do during an LFF trip with big headline films first thing every morning, so the idea of staying out late for an unknown quantity when I have deadlines to hit and sleep to grab never motivated me much to buy a ticket. But that’s not to say I didn’t ever try to get lucky in the public screening ballot allocations only to come up short each time. I’ve even kicked myself over missing a few of them: Lady Bird in 2017, Uncut Gems in 2019, Green Book in 2018… ok, maybe that last one was actually a bullet dodged and I knew so even at the time.

But this year, on my fifth go-around, I had gotten in. More accurately, my BFI Critics Mentorship Programme got me and the members of our posse who could be bothered to stay up/didn’t need to go back home first thing in. Perks of the package. Fevered speculation ran rampant as the night drew nearer, especially once I finally got to meet up with friends outside of the mentorship bubble to canvas their guesses. Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel seemed like a strong possibility – given the prestige buzz it was accumulating, it having done a few other festival rounds beforehand, and Scott being a British director – although a muted one since it was due for general release four days later. But, wait! What about House of Gucci, that other buzzed-about Ridley Scott movie? What a coup that would be! Alas, the movie was yet to premiere anywhere so why would it do so as a secret screening? That’d be counterintuitive, despite the restorative life 150 minutes of Lady Gaga’s Italian accent would’ve given me. Similar reasoning threw cold water on hopes of seeing Paul Thomas Anderson’s Liquorice Pizza. Hours beforehand, horrible rumours that Joe Wright had been seen around the festival emerged, bringing with it the threat of his musical Cyrano adaptation.

Photo by Julieta Cervantes / Courtesy of A24

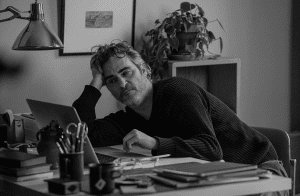

Taking our seats at 9:20PM, it turned out that all of us were wrong as the A24 logo gave way to a black-and-white close-up of Joaquin Phoenix. This year’s secret screening was C’mon C’mon (Grade: C), the long-anticipated and overdue return of Mike Mills, previously of Beginners and the outstanding 20th Century Women. Excitement at this, however, would soon give way to mild boredom, which would soon give way to frustrated disappointment. Much like Mills’ other films, C’mon is clearly a deeply personal work informed by some major event in his life, in this case most likely the maturation of his child with fellow artist and LFF alumni Miranda July. It’s the tale of a radio journalist, Johnny (Phoenix), called away from work to help his mildly-estranged sister, Viv (Gaby Hoffman), care for her (undefined) mentally-disabled son, Jesse (newcomer Woody Norman), whilst she attempts to get her bipolar husband, Paul (Scoot McNairy), the treatment he desperately needs but refuses to accept.

Yet, the film never once managed to achieve the greater transcendence it’s evidently aiming for. And I can tell that it’s aiming to say giant universal messages within such an insular and person-centric framework, firstly, because it keeps including these recurring segments of Phoenix in-character interviewing an assortment of children for their views on the state of the world and the possibilities of the future. You don’t keep returning to a device such as that after the initial introduction of what Jesse does for a living if you’re not trying to make a grander thematic point with it. But mainly I was able to deduce C’mon’s desire to reach some kind of universal transcendence from the fact that it rehashes the structure and presentation of Mills’ prior two breakthroughs, especially 20th Century Women.

Photo by Julieta Cervantes / Courtesy of A24

There’s a specifically rooted sense of place and time in the production design, Winter in New York predominately, similar to 20th Century Women. There are infrequent footnote-esque breaks where the protagonist reads relevant essays and prose to the segment of narrative we just witnessed, always cited in title cards, similar to 20th Century Women. There’s even a similar usage of cross-cut expositional editing, where characters will allude to prior events in their life in dialogue that the visuals will wordlessly flashback to as they talk; a technique I still really love, it’s good economical storytelling. However, despite using the same framework and techniques as Beginners and 20th Century Women, C’mon lacks the detail and specificity of those prior movies.

As clean and unashamedly New York as the cinematography is, it can’t help but be heavily indebted to films like Manhattan without bringing something unique of its own to the table besides artfully shot boxes of hotel rooms. Whilst that sense of place becomes a bit more generic and ill-defined when the narrative conspires to send Johnny and Jesse on a cross-country trip for Johnny’s work. Which may be kinda the point, the pair are just tourists in and out on a job with their crew, but I feel undercuts the attempted ‘pulse of America’ tone in those kid-centric interludes. As somebody with a mental disability (Asperger’s albeit not a severe version), I do really appreciate Mills’ effort to depict a kid with one in a manner that’s neither the most severe version imaginable nor all about how ‘difficult’ he is to care for. But Jesse still plays more than a little into both those tropes and the tropes of precocious children teaching disaffected adults to open up again, since his character doesn’t feel all that finely drawn despite Norman’s shockingly naturalistic performance and chemistry with the veteran Phoenix. (The fact that Paul is never seen outside of his bipolar episodes does not help, in that regard.)

Other than the rehash nature of things, that’s the problem with C’mon C’mon at large. It’s too one-note. Those prior Mills films balanced out their introspective and reflective stretches with equally as long stretches of joy and light comedy, digressions into the lives of supporting characters that made them feel richer and more alive, which mixed together to make those reaches for greater emotional transcendence legitimately cathartic and powerful. Dorothea’s monologue halfway through 20th Century Women remains the apotheosis of Mills’ entire creative career partly for that reason. Unfortunately, that depth of emotion eludes him here. It’s all morose all the time. In the screenplay, which lacks the tangible heart between its thinly-drawn leads to sell their connection. In the dialogue, which rarely has the rawness or surprising humour of his prior work, mostly settling for just being ‘pleasant.’ In the cinematography, which is cleanly composed but also entirely black-and-white for no discernible reason and resultantly makes everything look like a mediocre influencer’s Instagram. And especially in the Dessner Brothers’ extremely The National score, which is interchangeably beige and moody – a distillation of why I remain unable to get into that band the same way everyone else can.

Other than the rehash nature of things, that’s the problem with C’mon C’mon at large. It’s too one-note. Those prior Mills films balanced out their introspective and reflective stretches with equally as long stretches of joy and light comedy, digressions into the lives of supporting characters that made them feel richer and more alive, which mixed together to make those reaches for greater emotional transcendence legitimately cathartic and powerful. Dorothea’s monologue halfway through 20th Century Women remains the apotheosis of Mills’ entire creative career partly for that reason. Unfortunately, that depth of emotion eludes him here. It’s all morose all the time. In the screenplay, which lacks the tangible heart between its thinly-drawn leads to sell their connection. In the dialogue, which rarely has the rawness or surprising humour of his prior work, mostly settling for just being ‘pleasant.’ In the cinematography, which is cleanly composed but also entirely black-and-white for no discernible reason and resultantly makes everything look like a mediocre influencer’s Instagram. And especially in the Dessner Brothers’ extremely The National score, which is interchangeably beige and moody – a distillation of why I remain unable to get into that band the same way everyone else can.

To be clear, I don’t think C’mon C’mon is bad. In fact, I can even see how it might work or really resonate for other people – I know that I was in the minority of the critics who got into that screening by declaring it a misfire. But the aimlessness, non-specificity, re-treading of old creative ground, and monotony of the film couldn’t help but majorly disappoint me as somebody who adored Mills’ prior works. It’s pleasant but, not only did I want to get more from C’mon C’mon than that, I expect to get more than that from Mike Mills at this point.

CR: YANNIS DRAKOULIDIS/NETFLIX © 2021.

Following that absurdly late Monday finish, plus a combination of my being really behind on work (quelle surprise) and not being arsed to get up at 6am for a goddamn Kenneth Branagh movie, I took the Tuesday off. Slept in, recharged the mental batteries a bit, met up with non-mentee friends for drinks and shit-talk, saw no films for an entire day. A chance to reset and prepare for the oncoming onslaught of the rest of the festival. As frequently discussed, this year’s crop had been especially low-energy which was meshing badly with the exhausting nature of the festival churn, so a day of rest should’ve put me in a better headspace to fairly evaluate the rest of the pack. One of the major recurring soundbites from my critic friends who didn’t take that Tuesday off but still dragged their butts to Maggie Gyllenhaal’s feature writer-directorial debut, The Lost Daughter (Grade: B-), was that they were too tired to be able to properly appreciate another slow-burn psychological drama. I, fortunately, had no such issues – those would instead rear up later that afternoon during Luzzu – although that is sadly not to say Gyllenhaal’s film doesn’t do anything of its own to invite deflated ‘eh’ opinions.

But, like Lost Daughter, that’s starting at the end, so let’s rewind. The setting is an idyllic little village somewhere in Southern Italy, where academic professor Leda Caruso (Olivia Colman) has gone on a much-needed holiday to clear her head, renting out an apartment and travelling down to the nearby beach each day. But ominous signs manifest constantly to indicate that her stay isn’t going to be a relaxing one. The fruit in her kitchen bowl is rotten upon arrival. She wakes up during her first night to a giant dead fly on the pillow next to her. A pinecone drops onto her back whilst hiking, doing her a minor injury which remains for the rest of her stay. Most telling of all the alarm bells, the universal sign that things are about to go southwards, is the arrival of a rich obnoxious group of New Jersey-ians, constantly interrupting the peace of both beach and village with their entitled inter-familial squabbles and seeming neglect by a mother (Dakota Johnson) towards her young daughter.

CR: YANNIS DRAKOULIDIS/NETFLIX © 2021.

Leda cannot help but fixate on them during her days at the beach, especially the young mother, Nina, and the young daughter since Leda is carrying a lot of unresolved baggage. The kind that even the flirtatious advances of Ed Harris cannot curb. The kind pertaining to Leda’s own past as a young mother (played in flashbacks by Jessie Buckley) and the mistakes, negligence, and selfish choices she made which she sees potentially reflected in Nina’s actions. Slowly becoming consumed by guilt and self-flagellation, combined with unhealthy amounts of projection onto the deeply-unhappy Nina, as a tell-tale doll beats away at her psyche and conscience. Indie film editing legend Alfonso Gonçalves spends much of the first act working these flashbacks in like unwanted snapshots, here then gone again as Leda tries her best to dismiss them from her mind. There’s a real punch to times when this overworked and overstressed would-be academic snaps at the daughters she feels ill-equipped to look after which is made even more effective by the terseness of his edit.

Gyllenhaal, in general, conducts her various departments during this opening half with a assured hand. The visual editing, the self-penned screenplay (based on a novel by Elena Ferrante), the cinematography by Hélène Louvart, especially the sound mixing all come together to create an uncomfortable, leading atmosphere of potential darkness bubbling just under the surface at all times. There’s better supposition implanting, the inference that something is deeply wrong and unwelcome, than in most horror movies. This weight of and fixation on one’s worst moments in the past threatening to become all-consuming torture in the present, expertly communicated by Gyllenhaal’s direction. Also important to that effect: Academy Award winner Olivia Colman. She’s almost always incredible but she’s even more so than usual here, taking viewers on a tour of Leda’s full personality spectrum as her mind unravels and behaviour becomes more erratic in a manner which nonetheless remains completely understandable.

CR: YANNIS DRAKOULIDIS/NETFLIX © 2021.

Throughout, despite the omnipresent dread that Gyllenhaal conjures up, there’s a distinct lack of judgement going on from both the camera and screenplay. The leading editing and emotional cacophony would seem to set up a rather conservative attitude towards motherhood and a discrediting of the negative emotions and feelings that overwhelmed young mothers contend with. Instead, Gyllenhaal presents a somewhat empathetic and non-judgemental picture of those exhausted, frustrated, outright angry outbursts that mothers like Leda can feel. That in retrospect they may weigh heavy upon her conscience, even making her feel like a bad mother for some of the actions she performs, but the emotions fuelling them are still valid and don’t have to define one’s entire relationship to their children throughout the rest of their life. Sometimes, mothers need to self-care too. It’s surprisingly refreshing.

However, this does lead to Lost Daughter’s momentum sputtering out the further on it goes. Firstly because, as is often the case with dual-timeline semi-mystery narratives such this one, the second act goes heavy on the flashbacks to a degree that the present-day story slows to almost a complete stop whilst Gyllenhaal fills in the missing info. They’re strong and important flashbacks, arguably more so than the present-day story, with a really great Jessie Buckley performance, but the overall structure is very inelegant. Much more fatally… it all just kinda stops. There’s not a whole lot of resolution and the destination so arrestingly teased in the cold open turns out to be super anticlimactic. Befitting the non-judgemental depiction of uncomfortable truths, sure, but there is such a thing as making your ending too deflating. If anything, it actually makes that earlier pro of Gyllenhaal’s building of simmering tension a con since there’s no payoff to what is essentially misdirection. There’s a lot to recommend about The Lost Daughter, but you really need to be a “journey not the destination” type to avoid coming away more than a little unsatisfied.

COURTESY OF NETFLIX © 2021

Let’s switch to the small-screen. Television had a large presence at this year’s festival, either because the medium continues to make great strides in narrative and visual storytelling (if you’re an optimist) or because the festival programme was lacking in content and they needed to artificially inflate the numbers (if you’re a clever cynic). In particular, headlines were made by the premieres of Dopesick, Danny Strong’s star-studded ensemble look at America’s opioid crisis, and the third season of Succession, which literally everybody was talking about. I stayed away from almost all such premieres. Less so because of my militant belief that Film and Television are two separate mediums which shouldn’t aspire to be more like the other or evaluated on the same levels – yes, I am still furious about Twin Peaks: The Return being ranked on Best Films of 2017 lists, I am not a crackpot – but more because I don’t like evaluating works of art based on incomplete samples. Two episodes of television is not the same as a single complete feature film, so why would I rate or experience them as if they are?

But every rule has at least one exception and my animation stanning arse couldn’t ignore the opportunity to catch some of Maya and the Three (Grade: B for the first three episodes) on a big screen ahead of its release on Netflix – which, thanks to my heavily delayed turnaround of these pieces, was a couple of weeks back. Jorge R. Gutiérrez, the limited series’ writer-director, has been a dark horse favourite of mine and the Western animation community for many years. Starting off as a character designer on ¡Mucha Lucha!, creating the cult Nickelodeon series El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera, before directing perhaps the most underappreciated animated film of the 2010s, The Book of Life. His is such a fun, ambitious and, with the invaluable assistance of his wife and lead character designer Sandra Equihara, visually astonishing voice in the animation field who doesn’t appear often but is always worth paying attention to when he does.

COURTESY OF NETFLIX © 2021

So, tell me that Gutiérrez is back with another Mexican-centric fantasy tale – this one based on Mesopotamian and indigenous cultures in which a warrior princess (Zoe Saldaña) must go on a quest to unite divided kingdoms together against the vengeful gods of the underworld she’s the half-daughter of before they destroy humanity – and I will be there with bells on no matter the format. Maya wasted practically no time in affirming my decision to make an exception to my “no TV shows” rule, throwing a tour-de-force of visual extravagance at the viewer from pretty much the off. Most obviously, Equihara has outdone herself in the character design. Maya might be relatively unassuming, at least until she gets outfitted with some kick-ass armour and war-paint, but that actually helps ground the more outlandish larger-than-life designs of the other cast members. Her father being this huge hulking friendly giant who physically takes up a room just as much as his personality does. A sabretooth skeleton panther ridden by a conflicted pretty boy Prince of Bats (Diego Luna, cute meta-gag). Goddesses with shimmering wings adorned in tribal patterns that light up the sky and double as throwing knives. Gods whose bodies are made up of spheres that can detach and roll around to create massive earthquakes.

Those are just a taste of the unique character designs Maya and the team of animators at the now-sadly-closed Tangent Studios have cooked up, not even mentioning the gorgeous sets and props which surround them. Just like Gutiérrez’s prior works, it’s all based on Mexican and indigenous folklore which is sadly underrepresented in mainstream animation and the results speak entire essays about why diversity of voices in this medium are so needed. Sumptuous colours, artful boarding… and those are the dialogue scenes. When each episode’s big fight takes the stage… ooooooooooh, that’s the good stuff, folks! Smooth like butter, crisp and inventive in the staging, surprisingly intense for a kids show in ways that remind me of Avatar and The Legend of Korra, and just popping in a way that you don’t get from live-action films operating on presumably significantly higher budgets. Maya’s battle with Acat, the goddess of tattoos, in the second episode consistently wowed my jaded weary Day 11 of a Two-Week Festival self even before the characters started jumping out of the fake widescreen letterboxing on certain actions to emphasise their enormity. Visually, this thing is theatrical feature-ready and deserves to be seen on as big a screen as possible.

COURTESY OF NETFLIX © 2021

More astute readers may have noticed that I’m really fixated on Maya’s visuals, perhaps with trepidation about the quality of everything else as they wait for the other shoe to drop. Well, let me assuage those fears by saying that the actual narrative portion of Maya’s first third – there are nine episodes total, four screened at LFF but I had to dip out after three to make another screening – is good. There are charming vocal performances from the predominately Hispanic all-star cast, it’s willing to tease getting properly dark later on without always needing to offset those heavier moments via gags, and it’s so far a lot of fun. That said, the narrative and writing in general are pretty boilerplate; leaning heavily on convention, dynamics, and messages employed by almost every other entry in the kids’ fantasy animation realm. These first three episodes also suffer a bit from extremely frantic pacing, running at what feels like a million miles per hour to stuff everything into the half-hour runtimes. Not a dealbreaker, but a lot to take in all at once, as was the case at this screening.

But Maya and the Three is, at least for the first third, a really fun and entertaining slice of visual splendour with enough hints at a deeper and more thematically enriching tale which could be picked up in the series’ back-half. Plus, when those first few episodes do slow down a bit and spend some time letting these characters exist in ways that aren’t just about advancing the plot, it really helps expand and realise this sandbox into something more tangible. The gods we meet, in particular, are not only unique in their designs but in their personalities, displaying quirks and inter-personal squabbles which create the impression that these beings have lives of their own outside of the man-on-god smackdowns. When the imagination of the visuals also manifests on the writing side, Maya teases being one of Netflix’s best shows. I look forward to getting these dispatches out of the way so I can find out if the other two-thirds realise that potential.

Next time: Will Smith heads up the excellent Williams Sisters biopic King Richard, and Céline Sciamma breaks hearts yet again with the deceptively small Petite Maman.