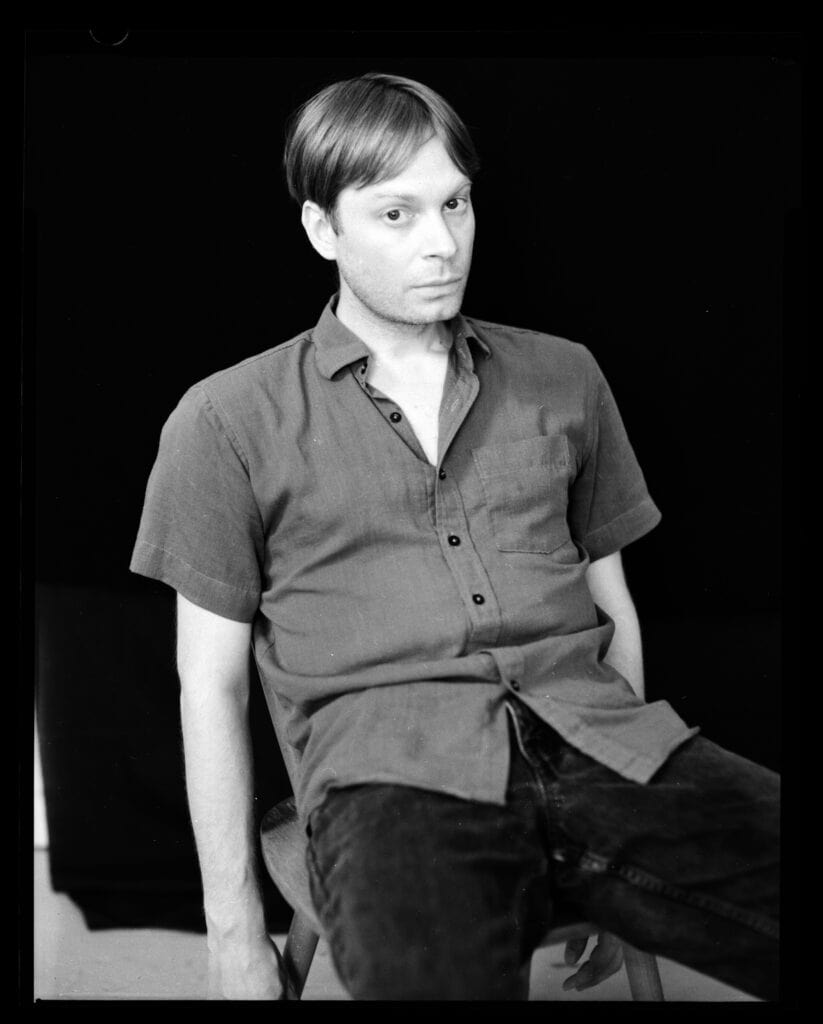

Making time after a fruitful day in the recording studio, Hendrik Otremba is ready for a rare interview in English. From lecturing creative writing at Fachhochschule Münster, penning critically-acclaimed novels in his native German, to exhibiting his artwork in galleries, the thirty-nine year old Deutscher is prolific to say the least. In music circles, however, Hendrik is typically associated with Messer. Since forming in 2010 the Münster quartet have evolved their sound from gothic post-punk to bass-driven kosmische rock. In this time Hendrik has embodied the post-punk frontman of yore; a brooding poet and narrator whose relationship with music is that of an outsider channelling their inner cosmos.

Indeed, the desire to work across multiple mediums fulfils a uniquely German concept of the gesamtkunstwerk. From Wagner to Kraftwerk, the term translating to “total work of art” refers to the synthesis of various art forms. In this respect the pastoral and industrial environments of Hendrik’s hometown – Recklinghausen – provided a perfect creative locus. Later, when studying at the University of Münster, he would finally transition from seminars to stages, uniting with Pascal Schaumburg and Philipp Wulf in Messer’s embryonic stage.

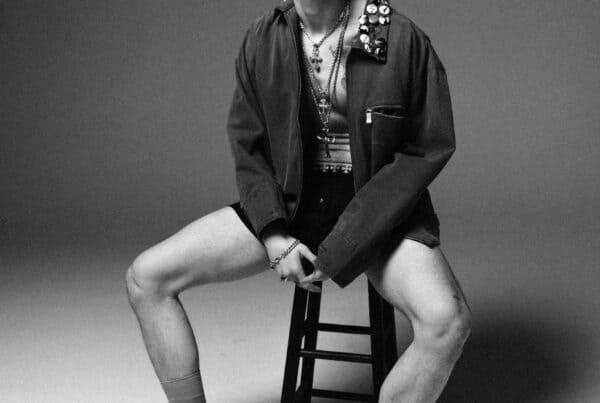

Photo Credit: Joe Dilworth

The trio’s initial aim was to create a “a band in the style of the Units.” Trading guitars for synthesisers, the new project subverted their previous effort – Tora Torapa – a “post-rock shoegaze instrumental thing” that saw Hendrik playing bass. Sooner than anticipated, the threesome found themselves longing for their trusty guitars. “We then asked Pogo McCartney if he’d like to be our bass player… so I lost my position and became the frontman.” Fourteen years on and the band’s lineup remains more-or-less the same, with Milek replacing Schaumburg from Jalousie (2016) onwards.

In the early days, Messer were true to their English namesake – “knife.” Sonically angular and lyrically direct, Hendrik took a “brutal approach to singing” that was conducive to more than a sore throat. On this topic, he quotes one of many important influences, Scott Walker: “To me, singing feels like a great terror”. Navigating this terror ultimately paved the way for an “ecstatic mode” of performance that would transform Hendrik’s life completely.

“When I was young, I was the one who stood beside the others. I was writing for myself, I was already thinking about songs, but the other guys were the people on stages.”

Picking up the microphone, naïve or not, paved the way for narration. As a songwriter, Hendrik’s style is characterised by dream-logic and opaque symbolism, as well as ample references to his literary work. In developing this artistic cosmos, Messer’s creative process has become one of “spheres colliding”. For their recent album – Kratermusik (2024) – this collision has solidified into a harmonious bedrock that marries poetic lyricism with the darker, momentous sounds of goth, dub, and kosmische.

Drawing inspiration from Germany and beyond, The Fall’s Mark E. Smith was an “important influence” owing to his grounded, yet surrealist approach to storytelling. From the wider German tapestry, Hendrik points to two Berlin acts – Mutter and Einstürzende Neubauten. The former are a veritable institution of German alt-rock that continue to resonate, while the latter have developed a global following through their eccentric sound. Towering above these unique acts, however, is a monolithic band within the German rock canon – Can. Although Hendrik’s style of sprechgesang resembles The Fall’s Smith more than Damo Suzuki or Malcolm Mooney, Köln’s finest avant-garde rockers remain the touchstone influence.

While initially hesitant to place Messer’s work within a national context, Hendrik acknowledges the intricacies of German as a musical language. “I realised from the very beginning that I find words that are not really singable, and so I wanted to bring the language into a singable form.” In turn, his unique German vocals are enhanced by a lyrical approach that demands questions rather than answers, drawing inspiration from the works of Andrei Tarkovsky.

“The connection between cinema and sound, music and song structures, is very important. With Tarkovsky, I like his very poetic way. His films have a plot that you might follow, but it’s more like a sphere through which he asks questions.”

Risky Manoeuvre

In Hendrik’s first solo project – Riskantes Manöver (2023) – Tarkovskyian meditations on life, philosophy, and identity are prominent throughout. Drawing from his own literary works, the album sees Hendrik recreating the interior dialogues of literature within musical form.

“In a novel there’s always this sphere in which someone more than you is talking… I wanted to figure out what happens when I try this in music.”

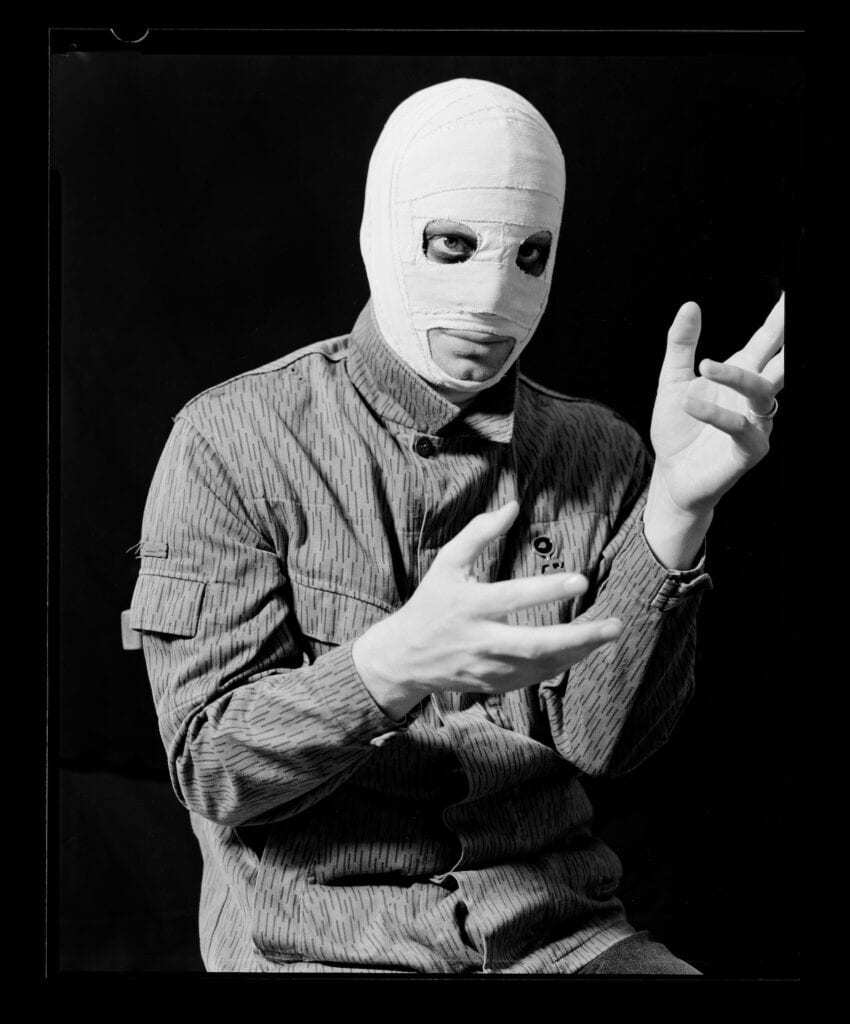

And so ‘66’ was created, the masked protagonist that narrates throughout. The design and name invoke two films released in 1966 – Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Face of Another and John Frankenheimer’s Seconds. Upon listening, I found myself immediately captivated by the album’s strong emphasis on atmosphere over concrete subjects. For Hendrik himself, verstehen (understanding) is to be felt rather than processed.

“The lyrics I write don’t really follow the idea of bringing a message. They are often influenced by dreams. Maybe that means they don’t need a translation, because even if you don’t understand the language, you understand the intensity.”

With lyrics concerning the artifice of identity, ‘Im Pelzmantel, Cretin’ is a definitive tone-setter that grips the uninitiated listener. Heavily inspired by Einstürzende Neubauten, the splicing of dark ambient and industrial production makes for a crushing declaration of artistic autonomy. Meanwhile, ‘New York II’ plays out as a Scott Walker-esque exercise in psychogeography, culminating in a rare guitar solo played by Hendrik himself. The rest of the project ebbs and flows like a well-defined chiaroscuro sketch; from austere piano ballads (‘Bargfeld’) to seven-minute noise-rock epics (‘Nektar, Nektar’), light and dark are in delicate contention throughout.

Converting a decade’s worth of sketches into an album, producer Christoph ‘Tiger’ Bartelt (Kadavar) helped to develop the initial demos into songs. Meanwhile, lifelong friend Alan Kassab recorded the majority of instruments, as well as guiding the production process. Working with the two revealed the uniquely liberating qualities of recording under one’s name:

“I felt more like the director of a movie. I was sitting in the chair, and I said, “We need light!”, “We need thunder!”, “We need beauty!”. The other guys knew and understood. It was the most intense collective process I’ve ever experienced.”

On the design front, Carolin Schogs and Joe Dilworth also played important roles. While Schogs designed the harrowing mummy mask, Dilworth captured 66 through their trademark photography. Both collaborations were aided by Hendrik’s vast creative network within his adopted hometown of Berlin. When pressured into choosing a favourite guest, however, Hendrik tentatively singles out the brief cameo from Alex Zhang Hungtai (Dirty Beaches). Offering instrumental support, Hungtai steals the show on ‘Nektar, Nektar’ with his wailing saxophone further intensifying the song’s apocalyptic descent.

Photo Credit: Joe Dilworth

Future Days

The appropriately-titled Riskantes Manöver (“Risky Manoeuvre”) ultimately speaks to Hendrik’s evolution as a frontman; an artist that is unafraid to incorporate various mediums as means to reimagining their sound and image. Reflecting on the overall project, Hendrik is open to recording future music under the same name:

“I always thought it would be a standalone work, but.. I want to experience something like that again. So maybe there will be another record but in, like, ten years?”

Although said in jest, ten years is a conservative estimate considering the current schedule. Before our call, Hendrik spent the day recording vocal contributions for upcoming bands from Wuppertal and Karlsruhe. Nowadays, Messer are experienced forebearers of a particular sound and movement within German post-punk, and Hendrik’s voice holds weight. Collectively, the passing of time has been kind; the quartet are happier than ever with the current set-up, and the roll-out for Kratermusik has, in Hendrik’s words, “surpassed expectations.”

Beyond music, the gesamtkünstler is busy writing a fourth novel – Der Gräber – building on Riskantes Manöver’s fourth track of the same title. After two years of concepualisation, Hendrik would be happy to “sit, write, and do nothing else, if it was possible.” Artists are often their own worst enemy, however, and research has already begun on a separate project that marries music and literary interests:

“I’ve been a fan of Can for more than 20 years now. I figured there might be ten words that define the band, so I’ve decided to write ten essays and with each essay I go through their history. It will be written like a Can song, where improvisation is knowledge, and I hope to have it translated into English.”

Behind family, these creative projects intermingle to create a never-ending source of inspiration and reward. Whether it’s an interview with Can’s Irmin Schmidt, performing with Messer in front of a rowdy audience, or quietly painting for the day, the same creative mindset remains. In turn, Hendrik’s future days will consist of developing these artistic pursuits, forming a multi-medium catalogue that defies definition.