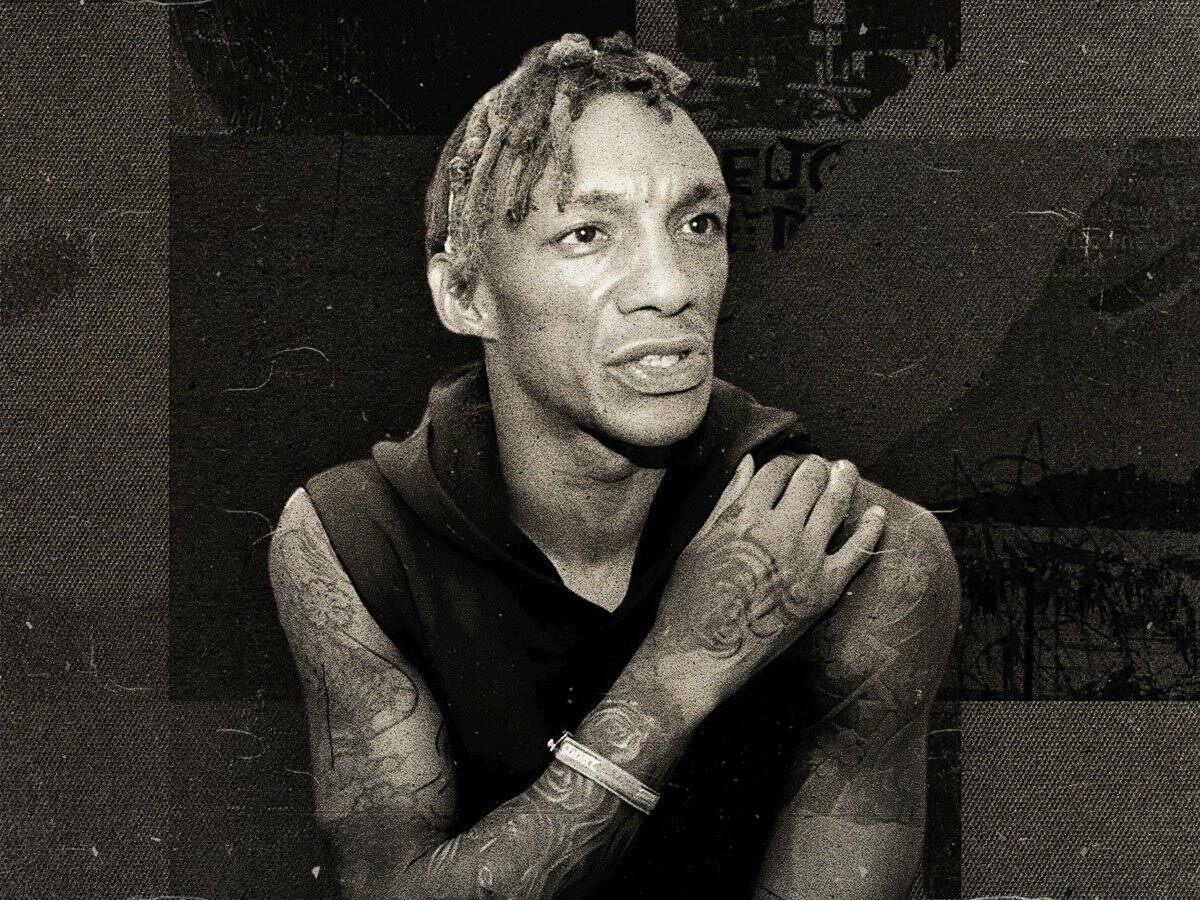

The man himself, Alan “Rat” Richards. Image sourced via Receiver Discogs page

As the headline suggests, Alan “Rat” Richards is a bonafide legend of the Bristol music underground. Inspired by a wide range of musical influences, he set out to create his own, regardless of budgetary constraints. Despite not seeing the same success as local contemporaries like Massive Attack and Tricky, those in the know know him to be just as musically intriguing and creative as anyone else in the scene, being involved in fantastic projects to this day. So, now, nearly 30 years on from his first release, I took some time to discuss his storied career, from past to present, and gain a heaping load of valuable insights along the way.

What was your starting point as far as a career in music? Were there particular influences in your youth or in adulthood that signalled to you that this was a viable path to take?

“I’m not sure I ever felt I was embarking on a career as such, more of a passion. When I started my interest in making music, it was at a time where mass unemployment and DIY punk ethos ruled the day, so a punk band it was. We were rubbish, and we argued a lot about who we wanted to sound like. This in a way was a good thing, as it gave me ideas of becoming a solo artist. First, I found a Roland TR-606 drum machine, and later, after learning I could use this to trigger a simple bass line on many a cheap synth, I had almost solved the argument and disagreement issue by effectively gaining an electronic drummer and bassist. I knew I could not sing, not for the want of trying, so I was still willing to work with someone with some acceptable vocals.”

I wanted to start off by asking about the Ratman stuff – Those first two EPs on Cup of Tea (ca. 1996) were great, very breakbeat influenced. What was your experience of creating them and putting them out with that label? I remember you saying your equipment was quite minimal at that time.

“By this stage, I’d been messing around for a few years with a tape machine, multi-tracking, and bouncing my drum machine and synth, just making dub electronic rhythms. Dub was something next to punk that, at the time, came hand in hand with influences of Public Image Ltd, Basement 5, The Clash, and any reggae I could get my hands on. Bristol has a big Jamaican culture, so going to the blues clubs or most house parties involved heavyweight dub sounds systems. My first interaction with jungle was at St Paul’s carnival, with a DJ just running hip-hop breaks albums over the top of classic reggae tunes. Hardcore and fast house music was already big, so breaks like ‘Amen Brother’ and ‘Funky Drummer’ just fitted seamlessly, especially with electronic dubs, as it was perfect to sync with breaks albums.

Still only having a basic drum machine and synth, and very basic sampler, I embarked on my own interpretation of what I thought it was all about. Realising it was never going to have high production sound didn’t phase me at all, because I was penniless, and not with very high expectations. To me, it was about the raw idea, like the punk ethos had always taught me. The Cup of Tea 12 inches happened due to the owner of the label hearing them and other slower music I had released earlier.”

© Ratman/Cup of Tea Records 1996

Tell me a bit about your time in Receiver with Rich Beale, and how that came together. ‘Chicken Milk’ was a great starting point, by ‘Teddy…’ it felt more like a full fledged “band” by that point, with Rich doing vocals a lot more. What was that dynamic like? Because you had a really interesting sound – trip-hop, breakbeat, indie, and all sorts went into it.

“The Receiver thing started with Swarffinger Records, and the owner of Cup of Tea, Pip, heard the 7 inch they put out (‘…And Then You Die/Irrational’). The genre “trip-hop” had already been coined by some London-centric journo, and everyone hated it, but when offered to get an album out, I jumped at it. The influences are from a multitude of loves, from punk and dub, hip-hop to jungle, space rock to ambient, soul and soundtracks. Fat Paul of Swarffinger Records also asked if I could remix a single called ‘Mood Master’ by his band, Pregnant. I said yes, and although he didn’t release it, he gave it to me to use on the ‘Chicken Milk’ album. After that, me and Rich started to explore other ideas over electronic beats and breaks. He also enjoyed the absence of arguing with bands, which he was used to (Head, and general Pop Group roadie, and artist). Rich came from an art-house, punk-indie stable which sounded original, and it all just clicked.”

Receiver (L-R: Rich Beale, Rat). Image sourced from Ratman/Receiver Bandcamp page

What caused the group to break down? It seemed like it was up and running and over relatively quickly.

“We were never really a group. We only performed once as Receiver, to a backing track, with me mixing echoey vocals, and a trumpet and trombone into it. Rich went on to develop a band called Applecraft, and then and up to this day, Don Mandarin, to which I have played synth, and made sound effects for live gigs. We’re still good friends to this day, and I still help him out with his various projects he’s working on.”

© Receiver/Cup of Tea Records 1998

You got the privilege of working with Diane Charlamagne during the Receiver days, and posthumously with John Paul – what was she like to work with? What did you take away from it, if anything?

“Working with Dianne was a dream. A friend of mine in London said a friend of his was working with her. I joked could he get her to sing for me. A few weeks later, he said “send me up some stuff and she’ll come down.” A month or so later, she’d done just that, for no money except me buying her a pub lunch. She even paid her own train fare. We recorded for about three hours, and she was off, and although I spoke to her and emailed, I never saw her again. She was a delight, and the most professional artist I’ve ever worked with. A big heart, and big soul, not to mention, a very big laugh. She was amazing. R.I.P. Dianne.”

Music icon Diane Charlemagne passed in 2015 following a cancer battle. Photo credit: Naki/Redferns.

Then, after Receiver, you moved onto, amongst other things, working on Dronesoul, which was a little bit of a stylistic departure for you as a rock band. Did you enjoy doing something a bit different with Rich again?

“Working with Rich on Dronesoul was great. As I’ve said, he came more from a rocky background. The music, along with the other musicians, just morphed into a stoner rock outfit. The repetitive, dub bass lines from me came naturally, but also, as I have mentioned before, it didn’t last long due to band disagreements, and everything I was originally avoiding in the first place. We played about 15 gigs, and enjoyed them all, but the public performance probably wasn’t for me.”

© Dronesoul 2015 (via video upload date)

Is there any difference between the way you write music for solo tracks or how you write for collaborative projects? Because a lot of your solo stuff seems a bit more dub/hypnotic oriented.

“I suppose when a singer isn’t involved, I go more to my happy place, and what I’m listening to or have been influenced by. A vocal is usually recorded with a BPM, so therefore can sometimes determine a genre of music for me to start at. Sometimes with vocals, I will make multiple songs and pick what works at the end.”

© Ratman 2020

Moving on more recently to your work with John Paul – How did you come to connect with John? What was it like working on the first album together – what’s he like to work with? Is it fairly collaborative?

“I met John Paul through Steve [Underwood], the then Sleaford Mods manager. Fat Paul of Swarffinger owns a club in Bristol and had put them on many times. Steve told Paul about JP, and what’s in his mind, but had no action, even though he’d done some tracks with the Sleafords. Paul kindly suggested me for the project, and the rest is history. JP is very easy to work with, as he’s more of a spoken word artist who gives me the freedom to do what I like with his lyrics. “You do your job, and I’ll do mine” is his mantra. Up to this point we’ve done hundreds of recordings, as he writes every day. In fact, it’s hard to keep up or remember what was good, or what was maybe to work on. It is collaborative, and it’s ultimately only if we’re both happy that we put it out.”

John Paul, described by Sleaford Mods as, “The Bard of Carlton”. Image sourced from John Paul Bandcamp page.

Have there been any ways in how, over time, you’ve modified or refined how you make tracks together? Like if something from the last LP maybe didn’t quite work, you felt like changing tact? Or is change more spontaneous?

“Maybe a little refinery, sometimes from feedback, but mainly making multiple tracks of different genres and styles, sometimes merging styles. When I first met JP, I asked what sort of music he wanted to do. He replied with, “The Specials meets Eric B with a Motown feel.” I assured him, maybe foolishly, that this was possible.”

© John Paul & Rat/Harbinger Sound/Environmental Studies 2020

You’ve had a big presence within the general Bristol music scene for so many years, like with your direct involvement in the Environmental Studies label. A legend, some might say. What would you say makes the scene in Bristol so thriving and special compared to other places, and how do you think it’s changed over the years?

“Music in Bristol, to me and everyone I know, and have known, has always been a passion as opposed to a profession, or making a living. For every Roni Size, there’s another 50 equally good artists, the same with Massive Attack and Portishead. Maybe they haven’t had the opportunities, funding, and belief, but I do know they have all got passion. The Bristol thing all happened at once, with the city awash with talent scouts from London coining genre names and trying to find the next Tricky. It was all rather sad in a way, but I’m so glad some talent got through to the big time.”

Tricky is one of the best-known artists hailing from Bristol. Photo credit: Far Out Magazine/Gregory Csatari

One of the coolest bands of many cool bands I think you’ve been involved with is Autobitch. They seem incredibly mysterious, but incredibly cool. Could you tell me anything about what it was like to work with them? Or whether they have any follow up plans?

“Not a clue really. I did some editing for them and Paul a while back. I know one of them has had a baby, so put music on hold.” (Update: Apparently Autobitch did an appearance in Bristol recently, at a night in a place called Strange Brew in Bristol).”

© Autobitch/Environmental Studies 2020

Finally, what’s next for you? Your most recent project was Lef’ Debris, an LP with JP, Jesse The Rebel Poet, and Nail Tolliday, and a really cool, collaborative effort. So, are you working on any new material, like with JP or Lef’? I know you’ve been wanting to tour with Lef for a bit at least, but what’s on the horizon for you that you can talk about?

“I’ve been doing a 2-step garage project with a friend called Rob, but still waiting to put up the site with releases. I’ve also been working with a friend of Jesse’s who is a poet and has cerebral palsy. It’s been really good fun, and great to get his expression across. He’s using an AI voice that I can cut up like JP’s voice. I’m still doing the Lef’ Debris stuff, and occasionally make music just for fun. The older I get, the more financially broke I seem to become, but the passion for making music never stops.”

© Lef’ Debris 2023

Thank you so much to Rat for his time. You can keep track of and support his releases on his Bandcamp page, as well as Lef’ Debris’ and John Paul’s pages. (Links in itallics).